By: Gabrielle Posner

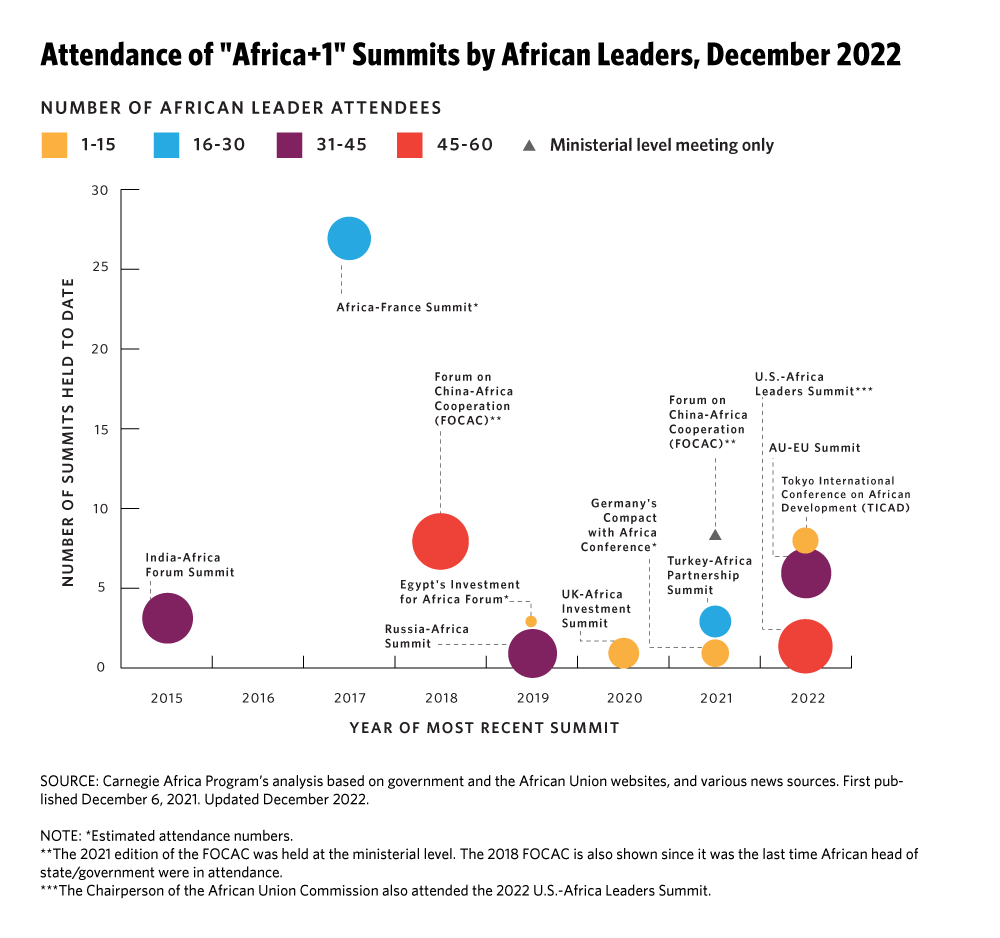

The new United States government strategy towards Africa represents a shift many are calling “seismic,” “unprecedented,” and “paradigmatic.” Released in August 2022, the Biden Administration’s U.S. Strategy Towards Sub-Saharan Africa centers trade and investment as the key levers for U.S. engagement with the continent, a deviation from the traditional aid-based approach. It also articulates a commitment to “African agency.” The White House subsequently held the second U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit in December 2022 that drew delegates from 49 African countries and the African Union, as well as members of civil society and private sector stakeholders. According to U.S. cross-agency initiative Prosper Africa, the U.S. Government has helped close 1,100 deals across 49 countries for a total estimated value of $65 billion since June 2019 as a part of its policy efforts to promote two-way trade and investment for mutual growth. High-level U.S. officials – including Vice President Kamala Harris, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, Ambassador to the United Nations Linda Thomas-Greenfield, and Secretary of State Antony Blinken – have traveled throughout the continent at a notable “frequency of outreach.”

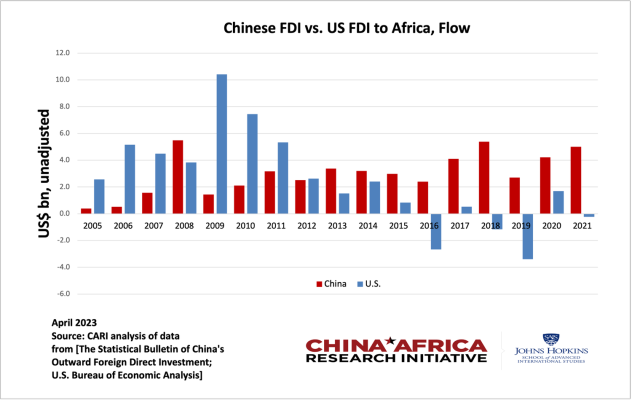

While rarely, if ever, explicitly said by Biden administration diplomats themselves, it is clear that the U.S.’s frantic, sudden interest in business engagement in Africa is a strategic move in its great power competition with China and Russia. Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) towards Africa has steadily increased since 2008, from $75 million in 2003 to $5 billion in 2021. China surpassed the United States as Africa’s single largest trading partner in 2009.

Moreover, in April 2022, the U.S. witnessed the power of the African voting bloc in the United Nations when many African countries remained neutral in condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. 15 African countries abstained from the vote, including Ethiopia, Guinea, Mozambique, Sudan, Uganda, Zimbabwe and the Republic of the Congo. Eritrea and Mali voted alongside Syria and North Korea not to condemn, which may indicate anti-Western sentiment. This moment was a “wake up call for Washington.” Washington is starting to realize that if it wants to maintain its leadership in global affairs, it must strengthen its efforts to earn African allyship.

The United States is late to join other global players that have significantly invested in their relationships with African countries over the last decade. Many of these international players have outpaced the United States in winning the allyship of African leadership through effective strategic communications, a critical tool for soft power diplomacy. In emphasizing South-South solidarity and non-interference with domestic affairs, China has become a rising soft power player in Africa. Meanwhile, America is teetering from its pedestal as a leader globally and on the continent. The 21st century gave America a soft power hubris that was uncontested – until now.

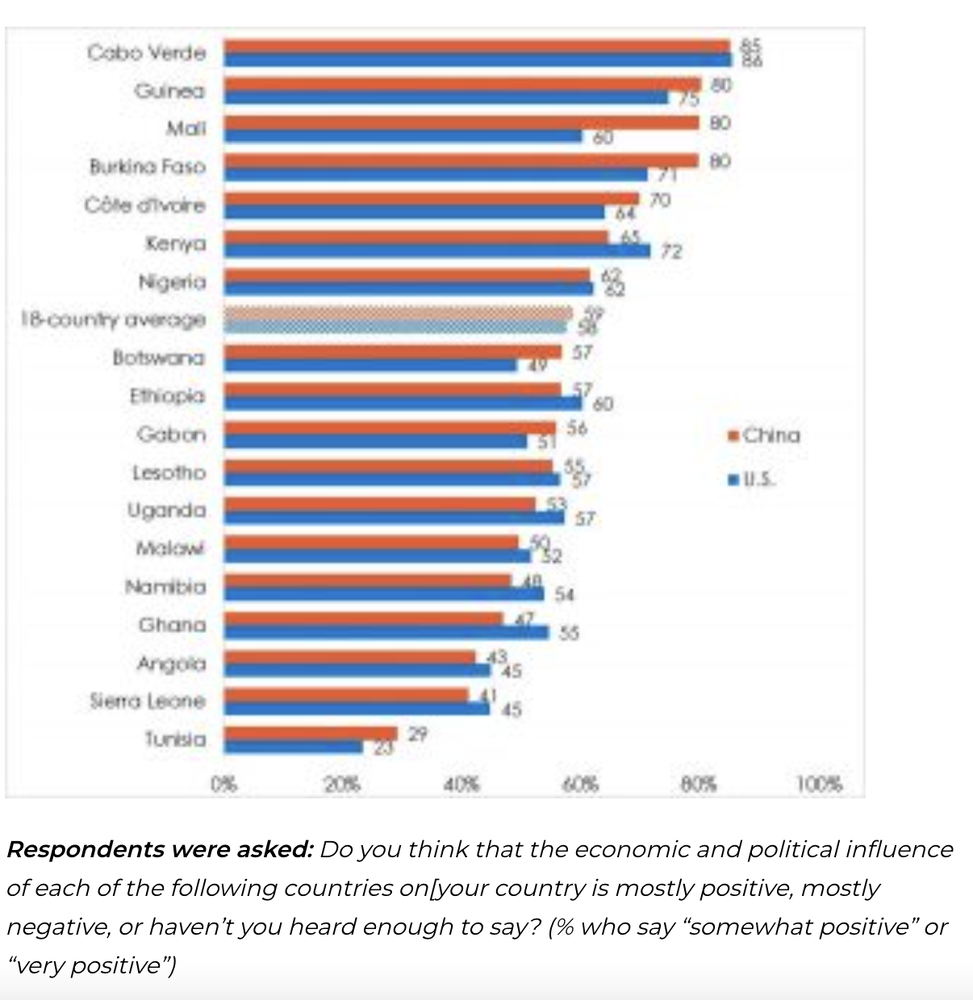

Now, China is catching up to the United States in popularity on the continent. A 2020 Afrobarometer survey found that 21% of respondents say China’s influence is “somewhat” or “very positive,” and 58% say the same about the United States. Within each country, “the differences between views of China’s influence and U.S. influence are quite small,” Afrobarometer’s Joseph Asunka writes. The difference is also shrinking; AidData’s BRI Perceptions Survey revealed that the vast majority (66%) of African leaders interviewed view China more positively than previously. U.S. Deputy Commerce Secretary Don Graves acknowledged that, “We took our eye off the ball, so to speak, and U.S. investors and companies are having to play catch up.”

The pressure is now on for the United States to advance its soft power agenda through effective communications strategies. In order for the Biden administration to effectively pursue commercial interests with Africa as a strategic diplomacy tool, it must pair investments with messaging that resonates with African leaders. American leaders can adopt the following three communications practices to demonstrate to the African people and its leadership that the United States remains a strong trade and investment partner amidst a competitive global arena.

“The U.S. has let our strategic communications capabilities atrophy at a time when we need them most to compete and win in a ‘contest for the future of our world'” – AidData, Gates Forum Paper

- Establish an intuitive brand identity to U.S.-African partnership.

The United States does not offer one cohesive nor consistent “American” package to African leaders. In one speech in Ghana alone, Harris jumped from “food security, the climate crisis, public health, and resilient supply chains,” to “security concerns in the Sahel,” to “droughts and floods,” to “empowerment of women,” and more. By contrast, Chinese FDI to Africa is well known for one thing: rapid infrastructure construction, such as highways, airports, and stadiums. Some find value in the American approach; Cameron Hudson of the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) argues that “Washington is really showing that it isn’t just one thing that we care about. We care about the waterfront of issues.”

From an African perspective, however, American priorities are unclear. Professor Ken Opalo calls on the U.S. to “have a clearer ordering of priorities (with commercial relations on top) and communicate the same to all relevant agencies.” America can only effectively communicate its commitment to the “waterfront of issues” if it develops a coherent narrative on U.S. priorities. Without one, there will be a gap between what America cares about (everything) and what it appears to care about (nothing in particular).

The four year election cycle further risks America’s ability to brand itself when each administration changes its Africa strategy. For example, President Biden closed the conversations opened by former President Trump in free trade negotiations with Kenya. Vice President Kamala Harris calls Zambia home, one of the African countries Trump called “a shithole.” China, by comparison, does not experience democratic turnover, which affords it the gift of predictability to give to foreign leaders. It has established its “‘brand’ as a donor” and commercial partner through the Belt and Road Initiative and non-interference principles. In the absence of its own “brand,” the United States leaves an impression of hot-and-cold relations with Africa, which may push African leaders towards partnering with a known risk: China.

An American “brand” can demonstrate to African leaders that it has predictable terms of partnership and is committed to the continent over the short and long terms. The government should invest in developing its strategic communications capacity to streamline name recognition of government-wide foreign policy, such as Build Back Better World (B3W) and Prosper Africa. In addition, communications experts can distill America’s many priorities into a few key messages for high-level speeches and press releases. A clear and consistent partnership offering can motivate African leaders to turn to the United States as much, if not more, than it turns to China.

2. Concentrate U.S. investment in industries within its comparative advantage for export to Africa, regardless of Africa’s partnership with China in other industries.

The U.S. tries to combat China’s growing economic involvement in Africa by offering itself as an alternative. In 2018, Congress passed the Better Utilization of Investment Leading to Development (BUILD) Act, which turned the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC) into the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (USIDFC). The BUILD Act was “the most important piece of U.S. soft power legislation in more than a decade,” according to Daniel F. Runde and Romina Bandura of the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). Just a few months prior to the Act’s passing, OPIC (now USIDFC) invested $1 billion into the “Connect Africa” initiative to support projects in China’s key industries on the continent: transportation, communications, and value chains.

Then-Secretary Mike Pompeo admitted that these initiatives were meant to “offer a better alternative to state-directed investments and advance [American] foreign policy goals.” This strategic geopolitical move to crowd-out Chinese investment in Africa has paternalistic undertones. Many African leaders interpret America’s “with-us-or-against-us” approach as a reprimand for dealing with China when such mutual exclusivity is simply an illusion.

Rather, they welcome the menu of options of global partners and reject the notion that partnership equates to political alignment. Many view U.S.-China competition on the continent as a win-win, rather than an either/or. Ethiopian Ambassador to the United Nations Taye Atske Selassie Amde explains that both countries [China and America] … are equally important for Africa’s development. However, it should be known that each African country has the agency to determine their respective relationship and best interest.” President Hichilema of Zambia said in a joint press conference with Vice President Harris, “When I’m in Washington, I’m not against Beijing. Equally, when I’m in Beijing, I’m not against Washington. We have a globe we share…. It is easy to say, when the President of Zambia is visiting Pretoria in South Africa, he is against Abuja, Nigeria. That’s the logic. Not quite.”

An American-only approach will work against itself. The United States can only advance its trade relations with African countries if it focuses on sectors within its comparative advantage and rids the temptation to crowd out China’s share in other sectors. China excels in rapid infrastructure construction. For the foreseeable future, African countries will consistently choose China as their preferred infrastructure investment partner, as China has a proven track record of rapidly completing megaprojects before political deadlines. The United States excels in export of its technological innovation and sports and entertainment industries to Africa. Just as China has secured its role in the infrastructure sector, the United States needs to concentrate its investment partnerships in its industries most ripe for export to African countries.

3. Make trade and investment commitments that respond to what the average African actually wants.

The U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit announced $55 billion in “investment” over three years. Under the “Trade, Investment, and Inclusive Economic Growth” category, the commitments include $21 billion in lending through the IMF for “African resilience and recovery efforts” and $369 million in new investments in food security, renewable energy infrastructure, and health projects, alongside trade-focused initiatives like support for the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) and increased funding for Prosper Africa. If American leaders want to demonstrate their commitment to African agency and innovation potential, they must decouple aid funding from investment in their communications.

Development aid from America is not a top priority for the average African (and certainly not for non-marginalized African political elites). On average, Africans want the U.S. to reduce import and export tariffs and non-tariff barriers (NTBs), so they can sell more of their goods abroad and buy cheaper ones. They want the U.S. to expedite and ease the visa approval process, so they can attend a top university, meet with their business partners, or spend time with their loved ones in the diaspora. They want the U.S. to expand scholarship programs like the Young African Leadership Initiative in order to access American educational offerings. These commitments are the ones that will prove that the U.S. welcomes the two-way flow of both people and goods as a mechanism to advance U.S.-Africa relations.

The Biden Administration is starting to align American priorities with those of African leaders, but their messaging can better reflect this synergy. Effective strategic communications are an essential tool for a competitive soft power agenda in an evolving global landscape. By leveraging this tool, the United States can better communicate its shared priorities with African countries and position itself as a reliable and committed trade and investment partner. It can start by establishing a coherent brand identity, selectively promoting core industries, and responding to the policy priorities of the African people. The U.S. can only chart a new era of partnership with the continent if it fills the gap in aspiration and strategic communication.

About the Author

Gabrielle Posner is the External Communications Manager at Baobab Consulting and a Senior Associate at IDinsight in Nairobi, Kenya. She is an international development professional with experience in data collection/ analysis and multicultural strategic communications for clients in 5+ African countries, including funders, large NGOs, African parliaments, and private sector social enterprises. Her experience on the continent amidst changing U.S.-Africa relations has piqued her interest in U.S. initiatives to promote trade and investment in Africa.